Blois is somewhere we drove through many times before we moved to France, as it's on the road to the Paris airports.

However, until March '14 we had never visited the chateau, despite knowing that it is somewhere that really repays a visit with many treasures and some good renaissance architecture, both things of which we are particularly fond. So here are some highlights:

The chateau sits in the middle of town. It was purchased by Louis d'Orléans, brother of mad Charles VI, at the end of the 14th century under somewhat scandalous circumstances when he seduced the young wife of the previous owner. His son Charles inherited, but taken prisoner at the battle of Agincourt, he was held in captivity for 25 years. Finally in 1440 he was able to return to Blois, which became his favourite residence. He spent the next 30 years writing poetry and rebuilding the chateau, a reaction to the end of the Hundred Years War that was not untypical of his class. Then to everyone's amazement, he fathered a son and heir at the age of 71.

The son, through the death of his

childless cousin

Charles VIII, became King Louis XII and married his cousin's widow,

Anne of Brittany. Blois became the principle royal residence and the couple built a new wing and enlarged the gardens. Their daughter Claude, the next queen, was raised in the chateau and died there at the age of 25, worn out after giving François I seven children in 8 years. François added the most beautiful wing of the chateau and it became the model for subsequent Renaissance chateaux up and down the Loire.

Claude and François' politically inept grandson Henri III thought to sort out his troublesome rival, the charismatic Duke de Guise, by having him assassinated here in 1588. Soon afterwards Henri's mother, that tough old cookie Catherine de Medici died at the age of 69 in her apartment in the chateau. Twenty-eight years later, the dowager queen Marie de Medici was banished to the chateau by her son Louis XIII, at the end of his tether dealing with her endless scheming. After this he gave the chateau to his equally scheming brother Gaston d'Orléans, in the hopes of repairing family relations. Gaston employed the architect Mansart to build a whole new wing but his grandiose plans were ended with the birth of the future Louis XIV and Richelieu cut off funds to the now 'obsolete' prince. Gaston had expected to be king after his hitherto childless brother, but the surprise new infant put a stop to that.

In the 18th century the chateau was abandoned, and there was even talk of demolishing it in the early 19th century. Luckily, instead, it was given to the town of Blois and used as military barracks. The soldiers were surprisingly gentle tenants and the building was not significantly altered. Eventually a tide of Romaticism washed over the country and in the middle of the 19th century interest in the medieval and renaissance was at an all time high. Architects and masons were engaged for over 50 years on a restoration project.

During the early days of World War II, Blois, like every other town with a bridge over the Loire, saw a flood of people fleeing to the south to escape the German invasion. In June 1940 the town was bombed by the Germans and several fires started. The chateau was threatened and in order to protect it two grand neighbouring 15th century houses were deliberately blown up to halt the spread of the fire.

The staircase tower in the inner courtyard at the end of the Louis XII wing.

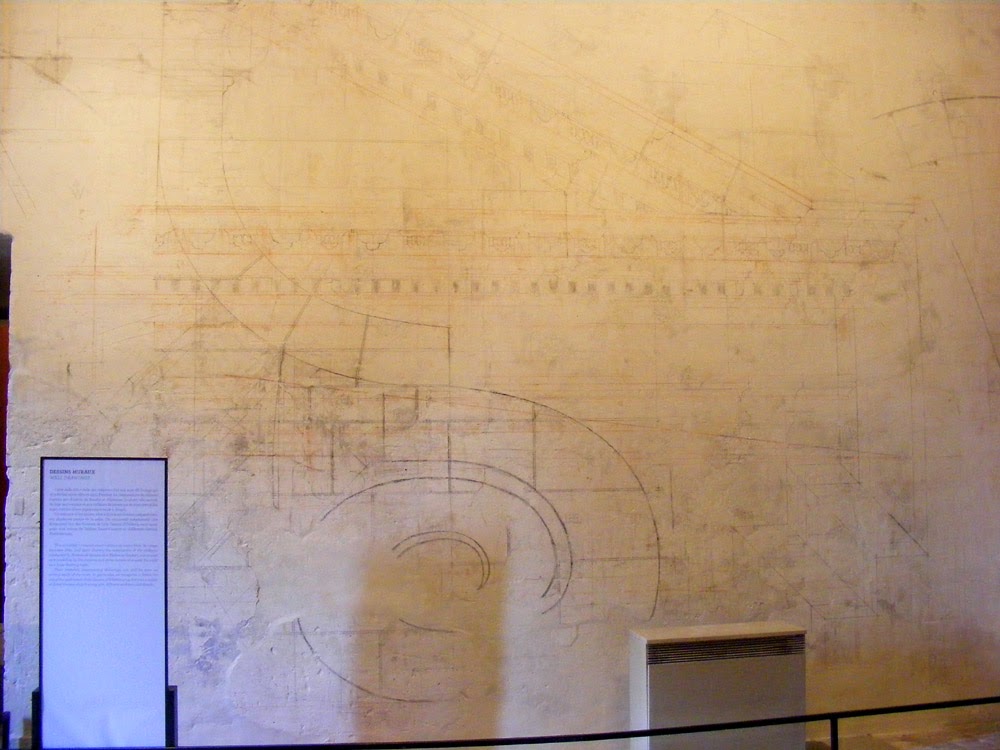

Masons' drawings from the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th centuries, done directly on an internal wall during a period of major restoration.

Detail of a 1873 majolica urn by Ulysse Besnard in the Musée de Beaux Arts section of the chateau. Besnard was the curator of the chateau and led a revival in the renaissance art of faience and maiolica (tin and lead glazed earthenware).

Louis XII's porcupine emblem.

The rather unusual symbol represents both his claim on Milan (who also used the porcupine) and his ability to aggressively defend himself 'both near and far' (because of the porcupine's supposed ability to project its quills).

The staircase in the François I wing.

The external walls of the apartments are decorated with Francois' emblem, the

salamander, another unusual choice of symbol, representing François' ability to 'survive the fire unscathed'.

The panelling in the private study built by François I.

This room would have been used for reading, dealing with correspondence, creative writing such as poetry, contemplation, and housing collections of curiosities. The panelling would not have looked like this in Renaissance times. Within months of its construction smoke from the open fire and candles would have dulled the gilding and blackened the wood. After his death, his daughter in law Catherine de Medici used the study.

This year there will be an exciting special

temporary exhibition at the chateau from 5 July to 18 October. Called Royal Treasures from the Library of François I, to celebrate the 500th anniversary of his accession to the throne at the age of 20. Most of the objects will be on loan from the National Library of France and will include his mother in law Anne of Britanny's Book of Hours (a

19th century facsimile is permanently on show at the Logis Royal in

Loches). It's a chance to see extraordinary things that are rarely exhibited.