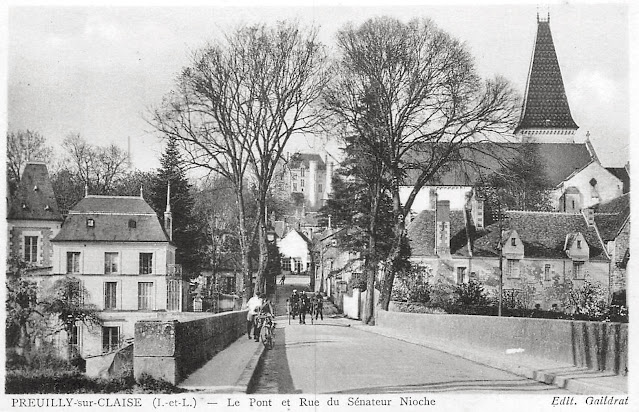

Recently I had a conversation with a Dutch friend about quinces. He wanted to know if quinces were used much in French cooking, because he loves them and in the Netherlands they are a forgotten fruit. He buys them in the Turkish grocers, or picks them up for free from someone who has some trees and can't sell the fruit. Finally he planted a tree of his own and this year got enough fruit to make a couple of pies. He says he particularly likes the combination of chicken and quince, but I'm not familiar with that dish. We also discussed that in many places there is a tradition of quinces being put on top of wardrobes to make bedrooms smell nice.

|

| Quinces on a roadside tree in September. |

Quince trees thrive in the Touraine. We don't have one in the orchard,

but our neighbour does, and as quince trees produce large quantities of

fruit, we benefit from periodic gifts of quinces. They are an old

fashioned sort of fruit and our elderly neighbour is delighted that I

like them and, perhaps more importantly, know how to cook them.

|

| Molten lava countered with a mesh lid. |

Being large, they are the last of the fruit to ripen and are ready in

late September - October. I poach a few, but most of them go to make

jelly and I run the pulp that

remains after straining for jelly through a food mill to remove skin

and seeds. It sits in the freezer until I get it

out to make quince paste.

|

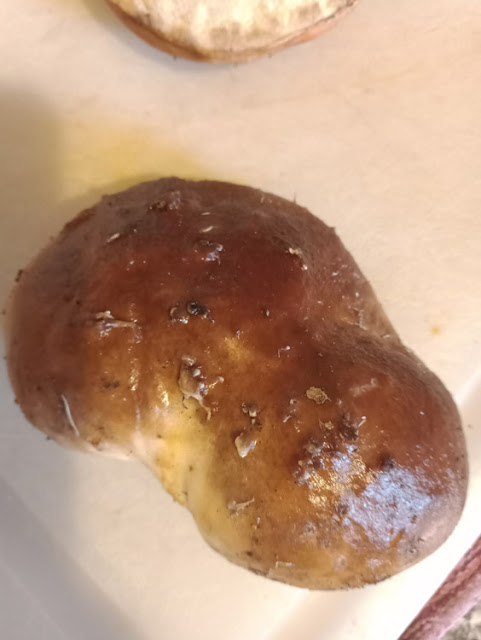

| The stiff dark paste just out of the oven. |

Quince paste seems to have originated in Turkey and from there made its

way to Spain and Portugal. In English language cookbooks it is often

called membrillo, which is the Spanish word for quince. Quince paste in

Spanish is called dulce de membrillo. The French for quince is coing, so quince paste is pâte de coing.

In England it is commonly referred to as quince cheese, and this is how

I first encountered it, at the farmers market I shopped at regularly in

the late 1990s-early 2000s. It is used both in a sweet and a savoury

context, as a counter to strongly flavoured cheeses or game and as a petit four or friandise with coffee. In France it is regarded as a seasonal treat, made in the autumn and served over the Christmas - New Year period.

|

| Starting to cut the block of paste into rods. |

To make it you combine an equal quantity of quince pulp and sugar in a

large boiler. Heat it slowly to dissolve the sugar and then simmer for

about 1.5 hours, on the lowest possible heat. It burns easily, so check

it regularly and scrape the bottom of the pan. Slowly the colour will

darken from orangey pink to brownish orange as it cooks. It is like

working with molten lava, both in its appearance and its capacity to

burn the unwary cook. You can't cook it with the lid on because you need

to drive a fair bit of water off. To protect against burns and splashes

I use a mesh lid on the pan, which allows steam, but nothing else out.

|

| All wrapped up and ready to store in the fridge. |

Once it has got thick and dark and you are having difficulty preventing

it from burning even on the lowest heat, transfer it to a baking tray

lined with baking paper. Put it in the oven at 50°C for another 1.5

hours to dry out some more. Then leave it in the fridge overnight to

cool completely and set. The next day tip it out on to a board dredged

in icing or vanilla sugar. Ideally, cut the paste into thick rods with a

wire, but a long knife will do. Dredge or roll these rods in sugar,

wrap in waxed paper and refridgerate. To serve, unwrap and cut into

cubes. Roll the cubes in vanilla, golden castor or raw sugar.

|

| Coffee and quince friandises. |

You can also bottle (can) it by putting it in sterilised jars instead of

in the oven. Close the jars and process in a water bath in the normal

way. This will give you a paste for spreading on bread like a jam, which

is very popular in Spain topped with Manchego cheese.

|

| A box of quinces from our orchard neighbour. |

And for

those of you interested in maintaining a certain sort of daily

regularity, quince paste works as well as the traditional prune.