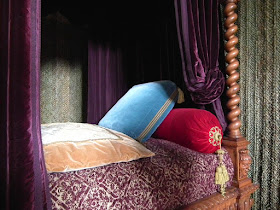

Philippe Lesbahy's bedchamber, with newly recreated canopied bed and rush wall treatment.

Sadly for Philippe, her husband and his family turned out to be wrong-uns, caught embezzling state funds, and despite her pleading, she was forced to abandon the Chateau of Azay le Rideau before it was finished.Now owned by the State and one of the historic properties expertly run by the Centre des Monuments Nationaux, it is perhaps the least well known of the big name chateaux in the Loire Valley. That's a shame, because the curatorial staff there do an excellent job and every year the presentation of the chateau features something new and exciting. They manage to be serious and scholarly perfectly combined with charming and fascinating.

The new rush matting in the Oratoire.

Their previous big project was to restore and open the roof spaces. This year they have recreated a Renaissance bedchamber, carefully based on historical sources, which they explain through the use of information panels, original paintings and a video. I knew the project was underway and involved creating new hangings for the bed, but it is much more than that, so it was a magnificent surprise to see the finished rooms when we took our first clients there in March.Taking their cue from a well known portrait of a royal mistress in the bath, the curators have commissioned hand made rush matting from an English artisan who is one of the few remaining professional rushworkers in Western Europe. The painting shows the walls of the room the woman sits in as lined with rush matting. The chateau sadly does not have the original painting on display -- that's in Washington -- but it does have a 19th century version that you can get extremely close to and scrutinise for details.The actual braiding pattern for the matting is based on a fragment found at Hampton Court Palace.

Detail of the rush matting.

Detail of the scalloped hangings echoing the decorative wooden bed frame.

Rush matting was a relatively cheap and easily available alternative to expensive carpets and tapestries. The purpose of all of these soft furnishings was to prevent cold radiating from the stone walls and to deaden sound in large echoing rooms. Housekeeping was easy -- dirt mostly just falls through, but it is a good idea to periodically mist with water to keep the rush in good condition and pleasantly aromatic.

The luxurious bed, with all details based on historical examples.

In addition to the rush matting, the curators have taken a 19th century Renaissance revival style carved bed and dressed it in recreated Renaissance hangings and soft furnishings. It is lush! Rich purple silk velvet has been trimmed with braid. Bolsters and cushions based on various historical references have been created and trimmed with gorgeous passementerie. Everyone concerned has done such a good job with this room. It will be a real attraction for the chateau, and I hope they are all immensely proud of it.

3 comments:

Interesting and informative post. I love the way the building historians of France are not afraid to 're-create' rather than 'restore'. This 19C cross-channel cultural battle between Viollet -le-Duc and William Morris (and SPAB) is very old, and the subject is a correct dialectic, but I myself delight in the confidence of the French conservators who remember that in the prime of these objects and buildings, they were new and sharp-edged, rather than crumbly and 'sepia-ed'.

I prefer the nodding heads of true bullrush to the stiff downy rods of reedmace. And the woven matting looks great up the walls!!

Very modern feel... rather than as old a style as it is.

Abbé: Personally I think the curatorial discussion might range around the subject on a different trajectory, but the end result is often much the same. In this case there were no surviving textiles and that drove the project. When a project requires new textiles, in both Britain and France, there is an understanding that they will jar on a battered old bed. I thought the decision to use a lovely 19thC bed in good condition was inspired though. A very good compromise. Rush matting never survives in any useable form (almost never survives at all -- the Hampton Court fragment is the only one I know of). It is always produced new for historic houses open to the public. I had a rush mat maker on my books at the NT and we used it in a number of houses.

Tim: The other nice thing about the rush matting on the walls is that it is remaining very aromatic. The stuff on the floor loses that much quicker.

Post a Comment